BOYFIGHTER feels deeply personal and emotionally charged. What was the initial spark for this story, and how did it evolve into a short film?

I was walking through New York City in July 2024, coming up on the one-year anniversary of my brother’s passing. I remember feeling incredibly heavy; emotional in a way I couldn’t quite contain. Tears welled up, but I have this thing about crying in public. I try to avoid it. So I started observing people around me, using them as a kind of distraction.

That’s when my eyes landed on something, slightly comedic, but oddly comforting: a father and his young son. The boy was dressed exactly like his dad, no shirt, low-hanging shorts, buzzcut, and he was mimicking the way his father walked, trying to match his posture, his rhythm. I was completely taken by them. In that moment, I knew I wanted to tell a father-son story as my next film.

When I finally sat down to think about what that story could be, I was still deep in grief. I couldn’t stop thinking about my brother. And my uncle. And my grandfather. And my great-grandfather. All these men who I love, died the exact same way. It almost felt like some twisted rite of passage. But the thing that ultimately claimed them was born from something else: survival, rage, abuse, neglect, systemic failure. That truth has always been hard for me to process. My brother died young, just like my only uncle who I never got to meet. And that reality tore me apart.

But as I sat with it, I realized something: that wasn’t my brother’s legacy. That wasn’t all he left behind. There was more, much more. His laughter, his love, the way he looked out for me. BOYFIGHTER came from that place. I wrote it to honor his struggle, but also to shine a light on his joy, and the bond we shared. That was the real inception of the film. And my hope is that it gives my family, and maybe others too, a little space to grieve our men, but also to love them.

You’ve mentioned the film is inspired in part by the resilience of the Mexican-American women in your family. How did their stories inform your approach to a narrative centered on masculinity and fatherhood?

Regardless of gender, the men and women in my family struggled. They only coped with that pain in different ways, or found different means of escape. While BOYFIGHTER explores themes of masculinity, I want to be clear that the spirit of the film is not bound by gender. At its core, it’s about human struggle, how trauma and survival shape us, and how that impact ripples across generations. The film is not so much about masculinity as it is about struggle.

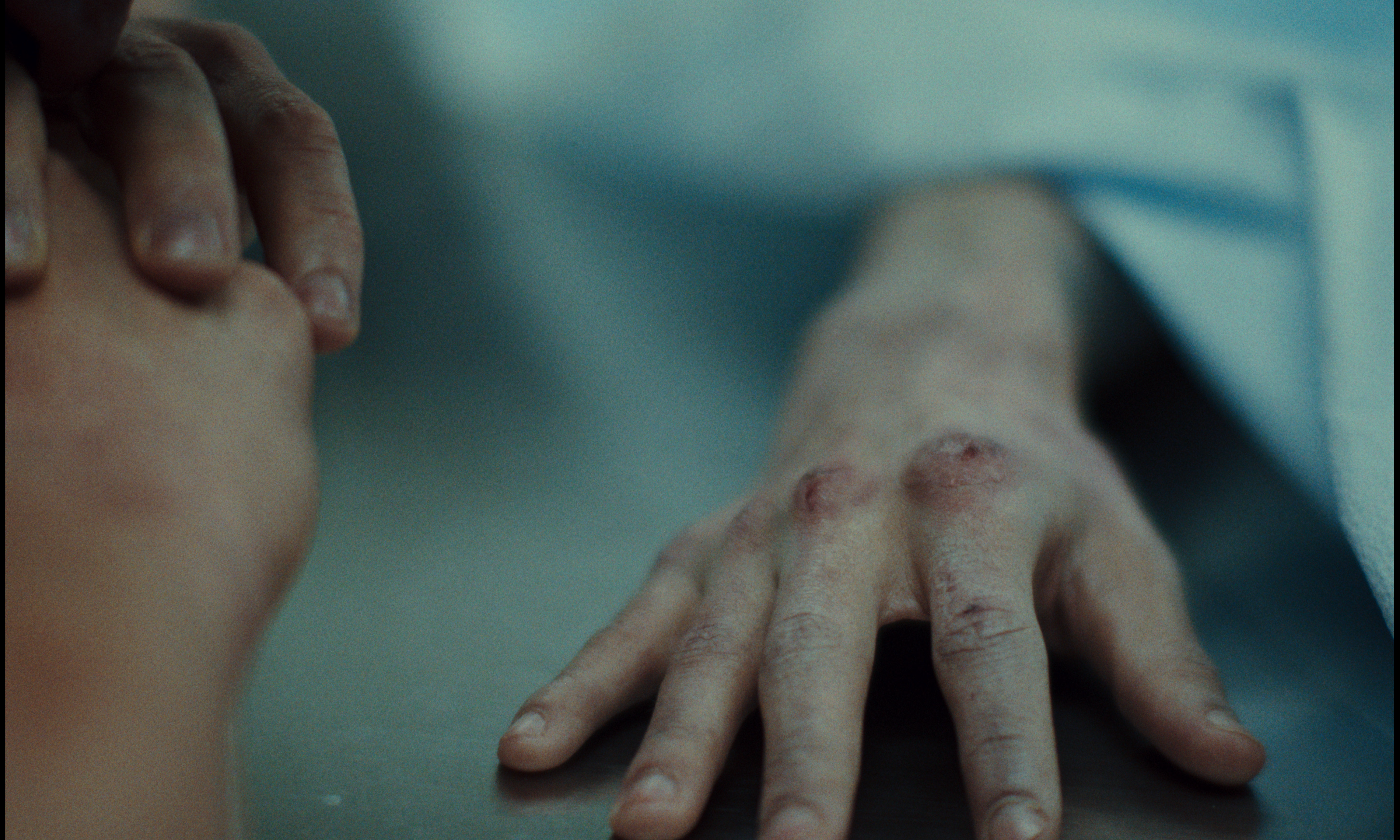

I’ve witnessed this firsthand in both the men and women in my family. The story is told through a father-son lens, but what drew me in was the opportunity to approach that dynamic with vulnerability and tenderness that these stories often lack. Diego, played by Michael Mando, is as much of his son’s mother as he is his father. I loved watching Michael explore the nurturing aspects of fatherhood, ones that live far outside the narrow confines of traditional masculinity. That sensitivity is where the heart of the film lives.

What drew you to explore the themes of inherited violence and emotional repression—particularly from a male perspective—for the first time?

I wouldn’t say BOYFIGHTER is the first film where I explore emotional repression, that’s actually a recurring theme in much of my work. But this was definitely my first real dive into violence. I felt compelled to confront it directly, largely because of the world we’re living in. Violence is all around us, it’s in our pockets, on our screens, embedded in our algorithms. We’re staring straight at it every single day. So many people are fighting for their lives right now, whether because of war, financial collapse, systemic oppression, environmental crisis. I don’t say that to be grim; I say it because it’s true.

BOYFIGHTER was a way for me to walk through that darkness and trace my own relationship to violence, and what it’s cost me. But more importantly, it was a way to search for the little patches of flowers, those overlooked moments of love and care, that still grow in the midst of it all. Those are the things I wanted to water. Thus, BOYFIGHTER.

Your directorial style in BOYFIGHTER is both lyrical and restrained. How did you develop the visual language of the film, and what were some key references or inspirations?

I think if you watch any of my previous films, you’d hopefully see certain stylistic through-lines. But BOYFIGHTER was a unique endeavor because so much of the story is rooted in memory. I wanted to explore a visual style that mimicked how we actually remember: when we think back to that one day with our fathers, or our sons, what is it that lingers? Do we remember that the sky was overcast? A particular shirt? The way the water looked cloudy after a storm?

Memory tends to come back in fragments and that’s what much of BOYFIGHTER is built on. Those little moments that, in hindsight, often signify the most important periods of our lives. The way we return to water, or an old shirt, or a summer storm and suddenly feel closer to the past, or to someone we’ve lost. That kind of emotional recall is comforting to me, and it’s something my director of photography, Matheus Bastos, and I were really intentional about capturing.

This was also our second film together, and by now there’s a trust and understanding between us. Matt has a way of immediately sensing the kind of emotional tone I’m after, and I trust his instincts completely. He’s one of the most talented DPs working right now, I really believe that, and I’m lucky to be building this kind of visual language with him.

How did you balance realism with emotional symbolism when crafting scenes of violence, silence, and reflection?

BOYFIGHTER is about capturing fleeting moments of tenderness, moments that might seem trivial at the time, but end up meaning everything. It’s about how those memories of love that live alongside our deepest regrets, our shame, our questions about whether we could’ve done more. That feeling of having let someone you love down, and for me, the most painful question of all: was there ever a way to stop what happened? Or was it always coming? If so, how do we move passed it? How do we move on? Those questions sting. And they’re all present in how we chose to film BOYFIGHTER.

But I didn’t want the film to feel purely experimental. It was important to me that the story, however fragmented it might be, still reach people. I wanted it to feel universal. While the film definitely dances around confusion at times, and memory is confusing, I think there’s an emotional undercurrent that runs through it. A connection

of love and grief that holds it all together. Even if someone doesn’t follow every beat of the plot, I hope they walk away having felt something. Maybe it incites them to make that call, to hug their lover, to take the time to really soak it all in.

The pacing is deliberate and intimate, often lingering in quiet moments. How intentional was that in the editing and direction? What did you want those silences to communicate?

Most of my work has these kinds of moments. I’ve always been drawn to spending time with characters when they’re not doing anything really, they’re just existing. No plot to push forward, no big twist to reveal. Just quiet stillness. For me, that’s where the most human part of filmmaking lives.

It’s in those moments of calm or solitude that you suddenly feel the weight of it all, the gargantuan reality of what it means to exist, to love, to lose, to cherish. Those are the moments that stay with me, and they’ll always be part of my work. Even when people think they should be cut, I stand by them.

Michael Mando delivers a raw, restrained performance. What was the casting process like, and how did you work together to shape his character?

I had the absolute pleasure of working with Joey Montenarello, a phenomenal casting director. He really took the time to sit with me and go through all my hopes and dreams for the character of Diego. Joey truly loves what he does, and it shows in his dedication. I owe so much of the casting success to him.

When I put together my list, Michael Mando was at the very top, #1. His past work had always stood out to me, there’s something so layered and textured in his performances. I knew I wanted to aim big and try to convince him to take a chance on me. Luckily, I was able to.

Michael had a very different process from any actor I’d worked with before. He leaned into solitude and personal exploration, rather than traditional rehearsals or detailed conversations. At first, that made me nervous. But once we started shooting, it became clear that this approach gave him incredible freedom.

I’ve never witnessed such raw talent up close. Michael has the ability to make bold, emotionally charged choices and to do so quickly. He can conjure such poignant emotion in a matter of seconds. It was honestly a gift just to watch it unfold on my little director’s monitor. I often had no notes. He delivered, every single time.

Of course, there were moments when we had to pull back emotionally, when we realized that holding something in could be more devastating than letting it out. But even that was a beautiful challenge. BOYFIGHTER has an energy to it that everyone on set could feel, it was hard not to go all the way emotionally. But Michael had the control, the instinct, and the depth to know exactly when to show, and when to conceal.

Can you speak to your collaboration with your producing team and how they helped bring your vision to life—especially as part of the Indeed Rising Voices program?

My on-the-ground producer, Mayte Avina, was truly my anchor. We had a major setback the day before shooting that completely derailed me. I was unwell—overwhelmed by fear, sadness, and doubt. But Mayte held me through those vulnerable moments. She reminded me of my strength and pushed me not to give up. If it weren’t for her, I honestly don’t know if I would’ve shown up to date one. That’s why BOYFIGHTER really is her film as much as it is mine.

I also had the support of my producers, Doménica and Constanza Castro, who called me during that difficult moment and reminded me of the story I set out to make. They encouraged me to lean and trust the team we

built in New Orleans, and to let the page do the work. I am deeply grateful for that support.

And then, to have the backing of a program like Rising Voices, that’s something truly special. It validates the years of hard work that it’s taken to get here. Their belief in the film, and the resources they provided to help it reach the world, have meant everything.

You’ve dedicated this film to your late brother. How did your personal grief and love for him influence your storytelling choices throughout the film?

Making BOYFIGHTER was a lot harder than I expected. I was honestly an emotional mess. Each day on set reminded me of the reality that he was gone and that I now stood in the position of telling his story. It’s one of those strange juxtapositions where you wish this wasn’t your reality… and yet you’re also grateful to be living it. To be turning grief into something meaningful. To honor someone you loved with all your heart.

My grief became both a gateway and an obstacle. It opened powerful doors to connection and vulnerability within the narrative but it also made it hard to literally move. When you set out to make something for someone

you love that much, there’s no way it will ever fully live up to what you believe they deserve. It can never quite capture the full depth of that love, or the full weight of that loss.

That was a hard thing for me to face. There were moments when I couldn’t tell if the film I was making was really doing what I hoped it would, if it was truly honoring my brother. But that became the most precious lesson of all: to let go of control. Let your stories become what they choose to be. We’re merely steering the ship. And fighting against the current, wishing for a different outcome… that can lead to drowning.

Once I was able to surrender, once I let go of the fear and simply leaned into the indescribable love I have for my brother, Richie, I felt free. I felt him with us.

Was the filmmaking process cathartic for you in any way? Did it reshape the way you view legacy or emotional inheritance?

I wish I could say yes. But the truth is, I’m still working through a lot of grief, pain, and unanswered questions, especially the question of why. That part hasn’t gone away. But even in the midst of my internal battles, I’m grateful that I can still remember the good. And ultimately, that’s what BOYFIGHTER is about.

BOYFIGHTER challenges traditional portrayals of masculinity and fatherhood. What conversations do you hope it sparks with audiences?

It’s hard to speak broadly about fatherhood, because it’s so unique to each father and so much of it is shaped by circumstance. But at the end of the day, I hope people walk away from BOYFIGHTER remembering that love is the most essential resource we can give our children. More than anything.

I also hope the film stands as a kind of gentle warning: our children are watching. They’re interpreting everything, even when we think they’re not. And when they don’t know anything else, they often re-create. We have that power and responsibility to show our children a different way.

How do you hope this film speaks to communities where emotional vulnerability—especially among men—is still taboo?

All I can really say, as someone who has lost, don’t wait to say the things you want or need to say. Say them. Feel them. You owe it to yourself and to each other.

You’ve worked across both television and film. How does your approach differ between the two formats, and where do you feel most at home?

I get asked this question a lot, and you may be surprised to hear that I genuinely love both equally. The shows I write are just as personal to me as my films, they’re both avenues to explore the world around me. My approach doesn’t really change much between the two.

The main difference is that television is built to last longer. You need to create a world and characters that can sustain three, four, even more seasons. That requires a different kind of narrative architecture. With films, especially in the indie space, I might have more creative control from start to finish. But in television if you’re lucky enough as I’ve been to work with remarkable collaborators, it’s incredibly exciting to bring a story to the table and watch it evolve through the perspectives and lived experiences of others.

That collaboration happens in film too, of course. All storytelling is a collective endeavor. But the process feels different in each medium.

I don’t believe I need to choose one over the other. Each offers its own unique rewards as a storyteller. I’m excited to keep telling stories I care about that feel impactful in both mediums.

What has the Rising Voices program meant to you as an emerging filmmaker of color, and how has it shaped your trajectory?

What I can say is that it was exciting to be part of a program that truly supported underrepresented voices without forcing us into a box. Rising Voices made space for nuance and the complexities of identity. It gave us the freedom to tell stories that felt genuinely exciting—not stories shaped by the pressure to stick to one point of

view or one kind of narrative. I’m grateful for that freedom.

After BOYFIGHTER, what stories are you eager to tell next? Will you continue exploring masculinity, or return to more familiar territory?

I have so many, too many, stories I’m dying to tell! BOYFIGHTER, the feature, is definitely high on that list. There’s still so much to explore in that world, and I really hope I get the opportunity to show everyone the full scope of what BOYFIGHTER can be.

I don’t believe in tying myself to just one type of story or one perspective. I’m always drawn to narratives that feel universal, even when they’re rooted in something specific. In television, I’ve been spending a lot of time in the crime-drama space, which has been really exciting. I’m also currently developing a period piece feature set in Scotland with the amazing producing company, Curly Top, and producer Alessandro Farrattini.

I’m working across a range of genres and tones, and I couldn’t be more grateful to the incredible collaborators who help bring these stories to life. But at the heart of all my stories will definitely be me and my family. Either way, I can’t wait to share more.

This was a long and engaging read. I thought the question on emotional symbolism was particularly interesting. I’m not a cinephile so this concept was new to me.

LikeLike